Charles Henry Neal was killed on the front line in Ypres on 21 January 1916. He was my paternal great-grandfather.

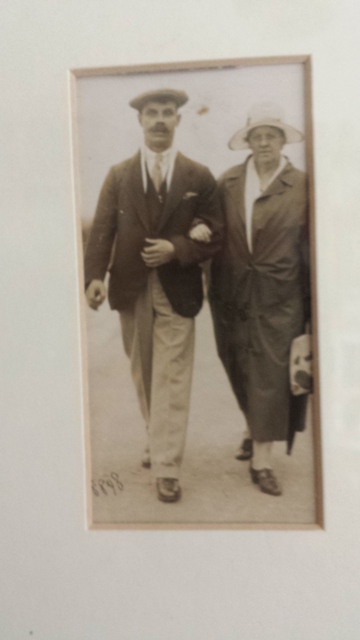

I never heard anyone talk about him because nobody I have met even knew him. My grandfather would have been only four or five when he went off to war and never returned. My great uncles, I never met any of them, whether this was through family disputes or just through people moving around I can’t say. My great-grandmother remarried after the First World War. She had a think six or seven children from her marriage to Charles and, as my mother said, it was difficult for a woman to find a man who could look after her. It was difficult to find a man who would “take her on” with so many children and of course fewer men as so many had died during the war. She found herself excepting a marriage proposal, perhaps nothing more than a marriage of convenience and even exploitation. The man she remarried, his name I don’t even know. There is a photograph of him walking along with my grandmother.

He looks like an actor dressed up as an evil character in a silent movie. And it was not for nothing that he chose to look or rather came to look like that. The stories that came down through my grandfather were that he was an evil and sadistic man. He frequently had resort to “the belt” and in my grandfather’s house the children were not allowed to sit down to eat at table until they were able to provide enough money to buy their own food. He was unkind and vicious towards both his wife and the children he inherited. There is some sort of explanation for this in that he had been I think something like a regimental drill sergeant in the First World War himself and had presumably seen and gone through some very unpleasant situations apart from those which he created himself.

So Charles Henry Neal lay in a grave at Ypres from 1916 to this day. I know that my grandfather Alphonso Neal, did visit his father’s war grave when he was an old man but I never had the opportunity or perhaps the interest to speak to him about this. My father has never visited this grave. At the end of the one-month holiday we have just taken as a family in France we decided to visit Ypres and find his grave. I instigated this not just out of a sentimental attachment but also as a way of introducing the children to their connection to the events of the First World War. Unlike me who grew up with parents and grandparents who had both been involved either as children or in active service or as isolated mothers in both world wars, my children, fortunately, have grown up with no stories of the war other than my fathers stuttered memories of fear and loss in the London bombings in World War II.

I don’t and didn’t want to frighten the children or to make them have to think about blood and gore and dirt and dismembered bodies. However I did want them to realise when they discussed the First World War in their school lessons which they will be doing for the next few years due to the centenary, that they had a direct connection back to these events.

We arrived in Ypres and booked into a hotel some 15 miles south on the north edge of Lille. I knew that every evening at 8 o’clock the last post was played under the Menin Gate and so we set off in the car to try and catch this. For a variety of reasons we arrived in the town just too late to find a way to the Menin Gate but we arrived in the main square to find it practically deserted. There was a very sombre atmosphere in that town something I associated with Flemish towns rather than the specific character of Ypres itself. The cafes were largely empty and there was silence unusual for such a large town. And then slowly people began to filter into the main square walking down from the service at the memorial which we had just missed. Several hundreds of people strolling quietly and sombrely back from hearing the last post and going into restaurants or climbing into cars and driving quietly away. Our children were not really aware of the nature of this event and were excited, tired and hungry. They were babbling and running around and shouting and doing everything against the sort of public propriety which is characteristic of Flemish towns in general and, from this experience, Ypres in particular. We felt like sores on the face of the town, blotches.

It always surprises me quite how Protestant the Flemish Catholics are! Quiet and industrious the place feels like an ideal Protestant town yet the religious nature of Flanders is one of a very Spanish and macabre Catholicism. Eventually we managed to feed our children and returned to the town the following day and took our bicycles to ride and find the cemetery where the children’s great-great-grandfather was buried. This was enjoyable and we found his grave. It’s not a big cemetery where he is buried. It carries maybe 1000 graves. Each one a clean hard limestone looking as if it had been sandblasted clean that very day. The grass between the rows of tombstones was neatly cut and small bunches of herbs of flowers had been planted in front of every grave. It was beautifully .kempt. The tombstones were quite small, probably only a couple of feet high and carrying a very plain inscription of the name, the regimental symbol and the date of his death.

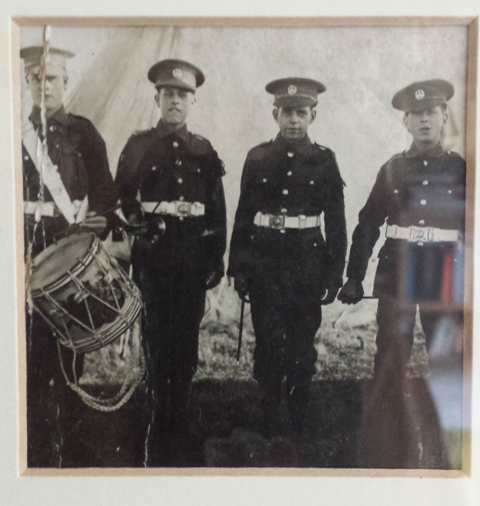

It made me realise quite how important memory was within the military. At the Menin Gate I was struck by a list of activities that were taking place each day. Groups were coming from England, the following day the boy’s choir from Camborne in Cornwall would be there, in order to celebrate every evening the last post and remember those who died in the great War. Naïvely I realised that the military and other organisations had funding available to allow and to encourage groups to come and take part in the celebrations. Teams of people either of military’s civic origin whose responsibility it was to keep them clean to keep them tidy and in order. I saw the description written on the Internet of the regiment in which my great grandfather served, the Buffs, where it was mentioned that they had been active in the third Afghan war. Suddenly it strikes me that the current one has been perhaps the fourth floor was at the fifth Afghan war? Was the recent war in Iraq the fourth Iraq war? The regiments have long memories and the military has long memories. The Buffs were originally a private regiment controlled by the particular member of the British aristocracy who eventually agreed to join with the wider United British Army. That is remembered in their regimental history. This particular regiments no longer exists but has its place within a larger regimental unit. But the memory is still there. When you look at the names of the commanders of the regiment you see names of families that are still active and powerful in politics today. Realising that the British aristocracy is tied so intensely and integrally to the order of the British military regime makes you realise how powerful and deep-seated is their power. How intensely ingrained the class system is into the functioning of a state which in the last resort maintains itself through military power.

And then the simple fact of being tidy. Of respecting the dead. My second cousin David has seen active service in Afghanistan. He is not dead but if he were how else could this be explained unless it was within the long trajectory of service, honour, death and all of these things made physical through the maintenance of graves. In fact in a family like mine, one with no great glory, no great power, my great grandfather’s grave sitting in a small cemetery just outside the centre of Ypres, is the oldest place to which I can turn to look at my family. The military give me that. And to those still in service it is the physical proof that there is honour in death on the battlefield. Having been brought up in the generation that reviled the First World War so profoundly, it is very uncomfortable to have these thoughts, to somehow think that to die in a foreign field might not be the worst thing in the world. So very very confusing.

My children enjoyed themselves in the cemetery. They were excited to find the grave like some sort of treasure hunt and stood reasonably dutifully to have photographs taken. And then they played and ran around and did somersaults and tried to pick flowers and argued and shouted and pushed each other. They climbed on the war memorial so they could stand up high with some sort of cross probably standing behind their heads. A part of me was shouting at them that they should somehow be more respectful as if they should hold their hands and keep their heads down. I saw quiet families moving through the town of the. Fathers perhaps who had been in the military. Their children well behaved, small girls with overcoats that were buttoned up, almost Edwardian children, walking along quietly and asking concerned questions to their father. And my children moved around noisily and in an unambiguous fashion did not think to show the quiet respect that this sort of order requires a view. Yet the other part of me looked at them laughing and thought that for my great-grandfather, who had no control over the circumstances which led to his own death, no responsibility in the occurrence of the war which killed him, what could perhaps be better than to have his great-grandchildren laughing above his body on this green grass.

I did not like the sombre atmosphere in Ypres but it did make it into some sort of giant church. The whole city feeling like a memorial. Shops selling souvenirs recalling the First World War. A artist installed in one of the buildings offering to make drawings of your deceased ancestor in First World War uniform. Shops selling items rescued from the fields of battle surrounding the city. And then the whole city itself like some sort of organic and wildly imaginative organic Lego set. The photographs that were attached to some of the memorials reminded me of the total destruction of the city of Ypres during the war. Yet brick by brick the buildings were rebuilt until you look at it and it’s almost impossible to imagine it had ever been destroyed. With Ella we looked at the buildings and this peaked even her interest. The vastness of the town Hall. The intricate work of a mediaeval fashion that had been reconstructed to the most minor detail.

It made me sad to think how we in Britain have been unable, following World War II, to reconstruct any of our cities in this fashion. It also made me sad because it felt that the city was some sort of two as well in itself. That is it been reconstructed, sandblasted to look clean and under it lay so many dead bodies. The great fear being that it would once again see such destruction.

Enough. That war is over. Another war came. And we live in the midst of the perpetual war.