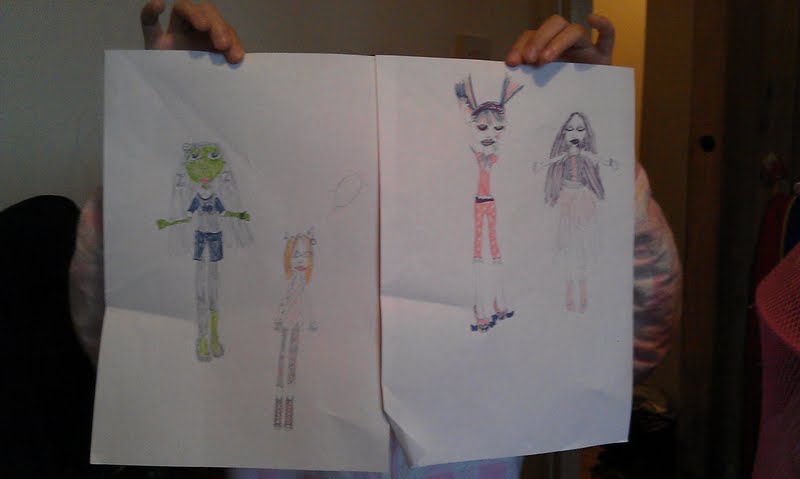

Around Christmas one of my daughters received a Monster High Doll or four. I’d never heard of them until a week before the 25th when I realised she had stopped obsessing about Moshlings and that there was a new gravity at work in her universe. We managed to change her gifts in time, shuffle a few around to the possible irritation of her younger sister and Hey Presto, come the big day Monster High emerged victorious. A very successful gift. She plays with it, attends to its needs, combs, cares and arranges everything. She draws portraits. Arranges photo-shoots.

Few other girls in her peer group seem yet to have these particular dolls but this morning I went to collect one of her friends to come and play. She too had received four Monster High Dolls for her gifts and in the car I was witness to a long and involved conversation where they seemed to be discussing the antecedents of the Dolls, that is their parents. My daughter said to her friend: “It’s funny how there are no Dolls of their parents.” What that made me think about was the astonishing detail with which children populate their games. I pay so little attention to the worlds my daughter creates around her toys but when I do, I realise that there is a whole social, moral and physical world that is build around them.

It is a craft to build such a world, one that is born of a practice of playing, of improvision, of making do, of collaborating not with me, the more of less (dis)interested observer, but with the dolls, their signifying features and with friends, collaborators in the flesh, more or less reliable but all the more reliable for that perhaps.

So I was left wondering where it is that the craft of practice relates to this? I thought that for collaboration to happen it has to be on the terms of the field, the child in this account. The researcher looking to craft a practice of collaboration, a dialogic ethnography, must allow the child to dictate the game to be played, must enter the world of the child even if that is not where the ethnographer, that is the I (paradoxically the object not the subject) wants to go.

A craft of practice needs must be open to being used. The craft of practice is thus a tool rather than a process? How do we develop a craft of practice? By picking it up and using it – but as we are it we must get carried away.

Posted from WordPress for Android