conspiracy

I’ve a good friend who suffers, if that’s the right verb, occasionally at least, from a sort of paranoid set of delusions that the world is, in the last resort, controlled by a set of illuminati, a conspiracy of powerful people.

I was an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge in the early 1980s where I had the opportunity to fraternise with a social class whose influence on cultural, political and economic life in Britain is without doubt.

When I mention this to my friend I realise how easy it is, or rather how easy it would be, for me to encourage the conspiracy theories to which she is prey. There is an eagerness to believe what is an easy conclusion that somebody is in control. My little dip into the water of powerful elites in and of itself gives me the opportunity to promote such ideas. In fact I could gain some sort of power myself through repeating such ideas. As if having seen inside the box I suddenly know that there are no limits to its capacity to hold the world.

But I don’t do it. In fact I don’t believe it. I don’t think that people are capable of that level of conspirator behaviour. Things are far messier than that. Outcomes much more difficult to second-guess. So I don’t play the game of encouraging belief in total control by an elite.

Corbyn 1

So Jeremy Corbyn has been elected as Labour leader. Immediately after the last general election I felt an urge to join Labour Party. I didn’t do it at the time but I sensed that some sort of moment of melting, of dissolution, had arrived and that there was something new to be built. I followed the emergence of the various candidates for the leadership including the slow and difficult recruitment of Jerry Corbyn. Once it became clear that there was some sort of swell of support for him I signed up and joined the Labour Party as a full member and duly voted for him in the leadership election.

I have found the reaction of the Labour elites to his election surprisingly disappointing. Perhaps it’s very naive of me but I’m genuinely shocked to see their lack of willingness, at least in public, to engage with what is clearly a ground swell of opinion amongst Labour supporters. Their failure to support their own supporters reflects very poorly on precisely the sort of attitudes to which Corbyn’s rise is a reaction.

The notion that somehow, because he is sixty-six years old and has been around for a long time, that his election is somehow a throwback to the past is profoundly faulty. Indeed it is his very longevity which denies this. He’s seen through the removal of old Labour and the emergence of new Labour. If anybody knows about compromise and understands the pragmatism with which political decisions resound it is a him. My immediate impression of Jeremy Corbyn was that he is somebody who will, in the end, not exactly compromise but perhaps more except the will of the people. In other words policy will be built on the support that is available for that policy. He will not block out particular opinions but will not block out radical opinions which has been the position of new Labour.

Seeing what has been happening around the new shadow chancellor it is encouraging to see that there is the opportunity to build a new set of frameworks for economic policy. The convergence of the Thatcherite conservatives with new Labour led to the complete decline of any sort of socialist politics. Such was the embargo on policy discussion that the very idea it might be possible to have some different approach to economic policy has been completely discredited. What the new election of Corbyn is offering, at the very least, is the opportunity to develop a set of thought out economic alternatives to austerity. The new Labour leadership is supported by a host of powerful intellectuals who, I suspect, will help build a scaffold around which a different sort of set of political imperatives can be structured.

validating artists

Short Notes

Well thank you for allowing me to take part in the workshop last week. I’m not an artist even though once in response to a question I asked an artist I was told that if I did what I was proposing that I’d have to accept I was an artist. But I never did it. Although it is still there in the back of my mind and I’m fully expecting somebody else to already have done it. In fact I think they have. Anyway.

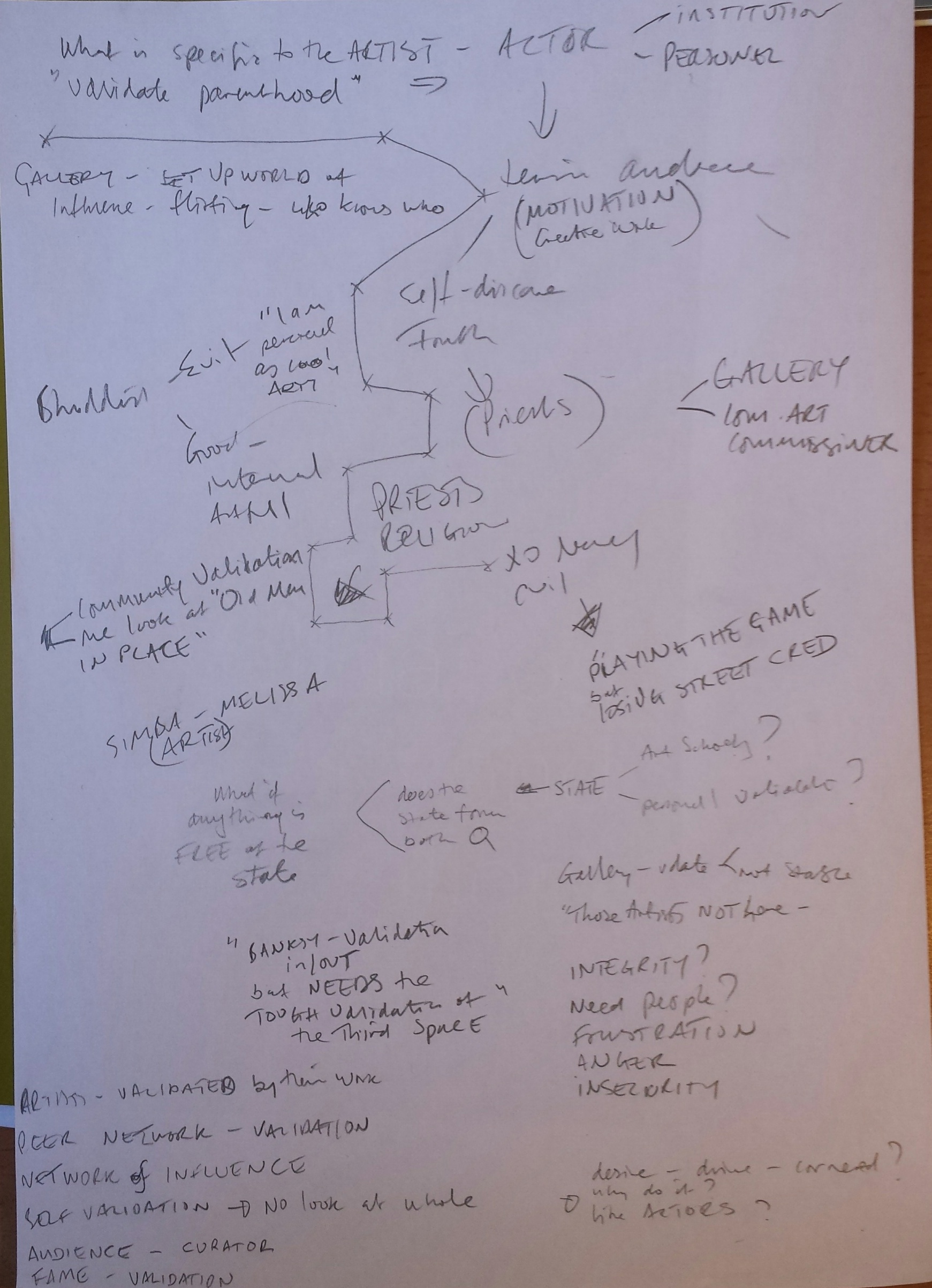

I made notes on a couple of sides of A4. I wanted to write them up immediately but was distracted and now, after the weekend, I can’t reproduce them clearly as I would have liked but I’ll write them down at least.

I must have been wondering what it was that was specific to the artist? Was there some formal comparison between validating the artist and validating parenthood? Somewhere in that question I was comparing the artist to the actor and seeing them both as part of an institution and having a personal journey. I wondered how much an audience was needed? What was the motivation? Was it just to create work? Something along the lines of self-discovery crossed my mind, the discovery of truth as if the artist might be in some way a priest.

Someone mentioned the idea of community validation. I liked that idea. It made me reflect on what sort of validation I might seek? I realise that in my life within my adopted community in Sheffield I am involved in some sort of process where community validation functions. The people who I suppose I could say I respect the most are those people who to an extent have done nothing other than just be here for a long time. I noted it down as the community validation of “old men in place”.

Buddhism: the evil Buddhist is the one who seeks to be perceived as cool, sublime perhaps, artistic; the good Buddhist the one who is artful.

Those nasty tensions between “playing the game” but “losing street credibility”.

What if anything is actually free of the state? Does the state practically form both questions? Does it generate the context of both art school and personal validation? Can it be escaped?

Banksy needed the validation of some sort of third space in order for the particular context of the work to exist. He didn’t validate that space by putting works of art there, the validation was done by myriad taggers. They remain the permanent outsiders. Forgotten. He Is the General. They are the foot soldiers.

What’s happened to all of the frustration? The anger? The insecurity? Where do they communicate with validation? Isn’t it true that you can just “blow it” that way?

The world of the gallery. A setup world of influence, of flirting, of who knows who.

Gallery validation just isn’t stable. It always begs the question about all those artists who quite simply just aren’t here.

Validation by work. By peer network. A network of influence.

And some sort of relationship between the audience and the curator.

Where is fame? What does that validate.

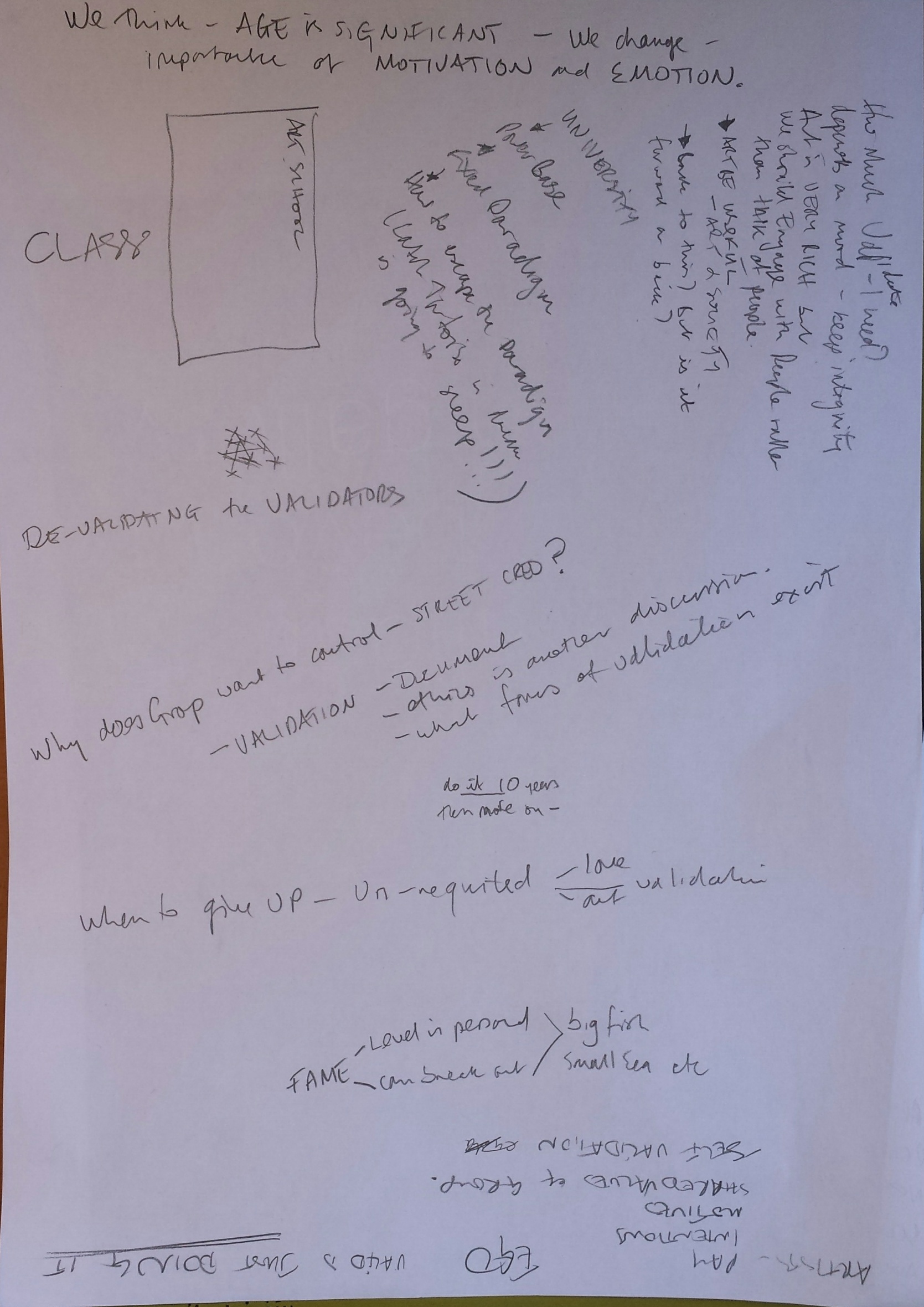

Then suddenly, of course, I remember that age is significant. We change with age. What happens with motivation? And what happens with emotion?

Did somebody say class? I don’t think they did.

How much validation is needed? How much is validation needed? It depends on the mood, how people are feeling. It’s important to maintain integrity. Art is a very rich thing but we should engage with people rather than talk of people.

Art should be useful! Art and society. We are back to this again. Forward or back?

The University offers some sort of powerbase. A fixed paradigm but how to escape the paradigms?

Here I started to dream whilst still awake; I caught a tortoise in my dream.

De validate the Validators! That was a call to arms.

Does this group want some sort of control?

Validation as a document; ethics is some other sort of discussion.

Someone reminds us of the story about doing it for ten years and if is not working, moving on.

So when to give up? If something is unrequited like love or art, is it unrequited validation?

Fame again: the level of fame is very personal. A big fish in a small sea and all that.

dishonesty

I wrote a literature review for an academic in the department on LEPs, Local Enterprise Partnerships. It is far from my field but the work was well recieved and I’ve been offered the chance to co-author an article. It’s given me a lot of pleasure to do some work which is appreciated. It’s also made me very tired of the empty compliments of some people who praise me up to the eyeballs but don’t follow it up with anything practical.

One of the surprising outcomes of the literature review was that I realised there was no proper ethnographic work on LEPs. One or two of the papers made passing reference to the idea of ethnography yet there was no account of the actual goings on within any individual LEP.

Whilst there is some analysis of the composition of LEP boards, some attempts at working with ideas of social capital, what is missing is an account that includes descriptive material which gives a sense of how LEPs work. What do they do? The literature offers few specific examples of actions by LEP boards. The literature gives no account of an LEP meeting. How many meetings are there in a year? Who attends them? With what regularity to people attend the meetings? Do people actually want to be on these local enterprise partnership boards? Is it done from a sense of civic duty? As might be the case in other ‘3rd sector’ organisations? How do people behave at these meetings? Are they engaged with the process? Do they find them boring?

so this was on my mind when I attended a conference yesterday that was concerned, partly, with LEPs. I spoke with another academic from my department, Aidan, and I was discussing with him this notion that there was no real nitty-gritty information being published about LEPs. He had given a paper about work projects in Leeds and his paper to had avoided, he admitted, actually giving honest accounts of what was going on. I was laughing and saying that information was being passed through nods and winks literally. A raised eyebrow here and a sideways glance there communicated to those people in the know that they were in the know along with the speaker.

It made me think of the known knowns as described by Zizek drawing on a famous speech by Donald Rumsfeld. Zizek was interested in the unknown knows, the category avoided by Rumsfeld. However I was drawn to the known knowns, That category of knowledge which we acknowledge but don’t actually speak. That is in a sense here what Ethnography offers and also why it can be transgressive. It, from the perspective of the polite academic, might appear impolite ought to be breaking agreements based on trust and privacy, to tell the truth of what is actually going on.

Mecca

fractidying

Cleaning the house and in the kitchen I get obsessed with crumbs and dust near the cooker and sweep it up for the umpteenth time. I realise there is no end to tidying.

Like investigations of social life. The political scientist in me looks at street layouts, the sociologist orders the whole house, the anthropologist gets to grips with a room (even under the bed), while the psychologist picks at crumbs and the psychotherapist dusts (manically).

The mote in the eye no less.

Outsider

I always feel like an outsider except when I really am one.

Utopia

When listening to a very short extract or rather the start of a longer talk by Zizek on utopia this is what I understood: that he understands discussion of utopia to be by its very nature a discussion of something which does not take account of material conditions, the contradictions, conflicts and struggles, out of which it arises. Therefore, I surmise, that the discussion of utopia is in fact the discussion of elements which in themselves are not corrupt, in themselves itself having no material expression.

what i said to the true believer

In discussion with a true believer I asserted that there is no more shame associated with the Western tradition than with others. That indeed this analytical mindset was one that enables the person to understand the viewpoint of another yet maintain their sense of being within that analytical framework. Other frames, other traditions but not all, cannot understand the other’s position as their own has yet to collapse. Our tradition emerges from collapse. The collapse of an ordered cosmos, the collapse of the order at the very least. The collapse of the soul perhaps. The collapse of the ego. Even the disappearance of heroic embodiment in favour of celebrity. It is the recognition of the possibility of collapse, its inevitability having already once happened, that forms the very freedom necessary to rebuild in a materially profound fashion, elements of the world which surround us. The heroic and true believer negates all this through a willingness to self-sacrifice, death not feared and it is true that death cannot be avoided. And it is true that the desire to maintain one’s eyesight after the onset of a debilitating eye disease may well be a desire to avoid that death. Death is inevitable but what we try to avoid is not the inevitable but things that are markedly evitable: high mortality rates in childbirth, frequent insurgencies of painful ways of dying. We do not play God. But God does not play God. God doesn’t play at all. We play that being people. That is what we are, scrawled out of the mud. A material. Consciousness as material.